Rifles, guns, revolvers and rifles, shots are among the most popular sounds in movies and video games. They are also some of the least common in our daily life (see 12 sound effects you think you know ). What is the link between film sound effects and actual sounds?

The physics

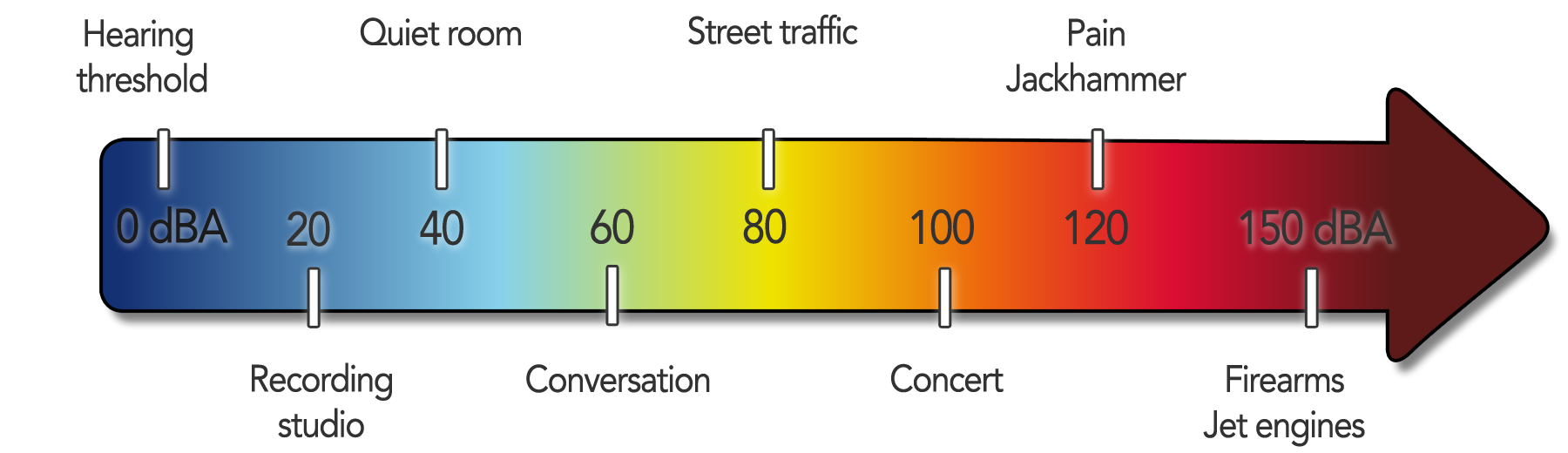

When you shoot with a gun, a large amount of energy is released in an extremely short time. At 1 meter, the sound reaches a very high level (called sound pressure level). Depending on the weapon and the ammunition, it can reach from 140 to 160 dBA. To understand what this kind of volume means, here is a decibel scale:

In movie theaters, the maximum volume in a properly calibrated room is 105 dBA . This is 45 dB less than a real shot. The ratio between these two sound volumes is: 45 dB = 15 x 3 dB. Energy is multiplied by 2 15 or 32768.

So in theory there is a 1 to 30,000 ratio between the sound level of a real shot and its representation in motion pictures. In practice, it becomes immediately clear. When I recorded for the first time in a shooting range, I was surprised to feel a shockwave throughout my body and to find the sound very loud despite the hearing protection. My mic preamps were set to the minimum, values I had never used. If we wanted to have such sound levels in theaters, we would need extremely powerful speakers. But that would be totally useless, except if we want to make the audience completely deaf.

If the experience of real sound is so different from fiction, how do sound designers make the viewer feel the same kind of emotion?

The solution is essentially psycho-acoustic: increase the duration of the sound to make it sound louder.

On the recording set

Sound recordists who work on firearms generally use multitrack recorders and several microphones. Some are placed close to the gun to capture a very dry sound and other mics are placed at a distance to record reverberation.

Here is for example the sound of a military rifle that I recorded 1 meter away. The sound is very short and has no character of its own. It could be a firecracker or finger snap.

It’s not the same isn’t it? Believe it or not, the two sounds have the same volume. Our ears are simply not sensitive to shorts sounds. They seem quieter and our brain does not have time to analyze them. The second sound, very reverberated, seems way more powerful and expressive.

Mixing different sounds

When designing sound, we often mix different layers. When we have multi track recordings with several microphones, we can make an infinite number of mixes with the different tracks.

Contextual sounds are also often added, such as mechanical sound from the breech, falling sleeves, etc. They are used to bring personality to the gunshots. In reality these sounds are often muffled because they are too quiet compared to the detonation. When we are not looking for realism but rather a particular emotion, we can use totally different sounds like cannon fire, explosions or even sounds that have nothing to do with guns. We work on the timbre of the sound.

Here is an example from Terminator 2 by James Cameron. This scene is the first confrontation between the two cyborgs, where we discover who is the ally and the enemy. To emphasize the power of the machines, the sound of the weapons is excessive. Notice how the reverb (which doesn’t match the place at all) amplifies the feeling of volume.